Understanding the Process and Benefits of Stump Grinding

Introduction and Outline: From Tree Removal to Living Landscapes

Trees shape safety, shade, drainage, and property character, so decisions about removal, stump treatment, and replanting ripple across years. Cutting correctly prevents damage, and grinding the stump unlocks space for fresh plantings, paths, or lawn. The arc from tree removal to landscaping and ongoing arboriculture is not a set of isolated tasks but a system: one move affects sun patterns, soil moisture, biodiversity, and maintenance budgets. Think of it like editing a long paragraph in a novel—every cut or addition subtly changes the meaning of the sentence after it.

This article starts with a practical outline, then expands each topic with methods, comparisons, and field-tested examples. We will map hazards, navigate permits, choose removal techniques, and show how stump grinding works down to the last chip. From there, we rebuild soil health and design, and finish with long-horizon tree care that pays dividends in resilience and beauty.

Outline of what you will learn:

– When removal is justified versus when pruning or cabling might suffice

– How to plan and execute safe removals on tight urban sites

– What stump grinding involves, including depth, cleanup, and replanting windows

– How to restore soil, redesign beds, and adapt to new sun and wind exposure

– Arboriculture strategies that keep new and existing trees healthy for decades

Why this matters now: urban storms are more erratic, insurance carriers increasingly scrutinize tree risks, and homeowners want landscapes that look good while supporting pollinators and managing runoff. Studies have repeatedly associated healthy canopy with cooler microclimates and modest rises in property value, often cited in the range of single-digit to low double-digit percentages depending on region and tree size. By the end, you will have a clear, actionable path from first assessment to the moment fresh leaves break bud on your next tree.

Tree Removal: Safety, Assessment, and Method Selection

Tree removal begins with a risk and value assessment. The core question is not “Can we remove it?” but “Should we?” Indicators that removal may be warranted include: irreversible trunk decay, large dead scaffold limbs over targets, root plate heaving, repeated storm failures, incompatible placement under utilities, and severe pest or disease damage with low recovery odds. Where a tree provides significant shade, screening, or habitat, alternatives such as pruning, soil remediation, or selective reduction may preserve benefits while mitigating hazards.

A structured assessment looks at three factors: likelihood of failure, likelihood of impact, and consequences if failure occurs. Targets include roofs, play areas, sidewalks, and service lines. Lean direction, prevailing winds, and soil saturation matter—waterlogged soils reduce root anchorage. Before a saw starts, create a plan showing drop zones, tie-in points, escape routes, and equipment staging. Personal protective equipment, stable footing, and clear communication are nonnegotiable; tree work consistently ranks among higher-risk trades, largely due to gravity, chainsaws, and unpredictable wood fiber behavior.

Method choice depends on space and defects:

– Conventional felling: efficient where ample clearance exists and lean helps the fall. Hinges and back-cuts must account for tension and compression wood.

– Sectional dismantling: the standard for tight lots. Workers lower pieces with ropes to avoid damage.

– Crane or lift assistance: valuable when decay makes climbing unsafe or when precision over structures is required.

Permits and timing can shape the schedule. Many municipalities require permission for trees above a certain diameter, and nesting seasons may limit work near active wildlife. Weather windows also matter: high winds or ice magnify risk, while dry, firm ground reduces turf and soil damage from equipment. Finally, plan for post-fall cleanup, stump strategy, and site restoration. A removal without a next-step plan leaves a safety win but a useability problem; the stump often becomes the pivot point for the landscape’s next chapter.

Stump Grinding: Process, Depth, and Practical Benefits

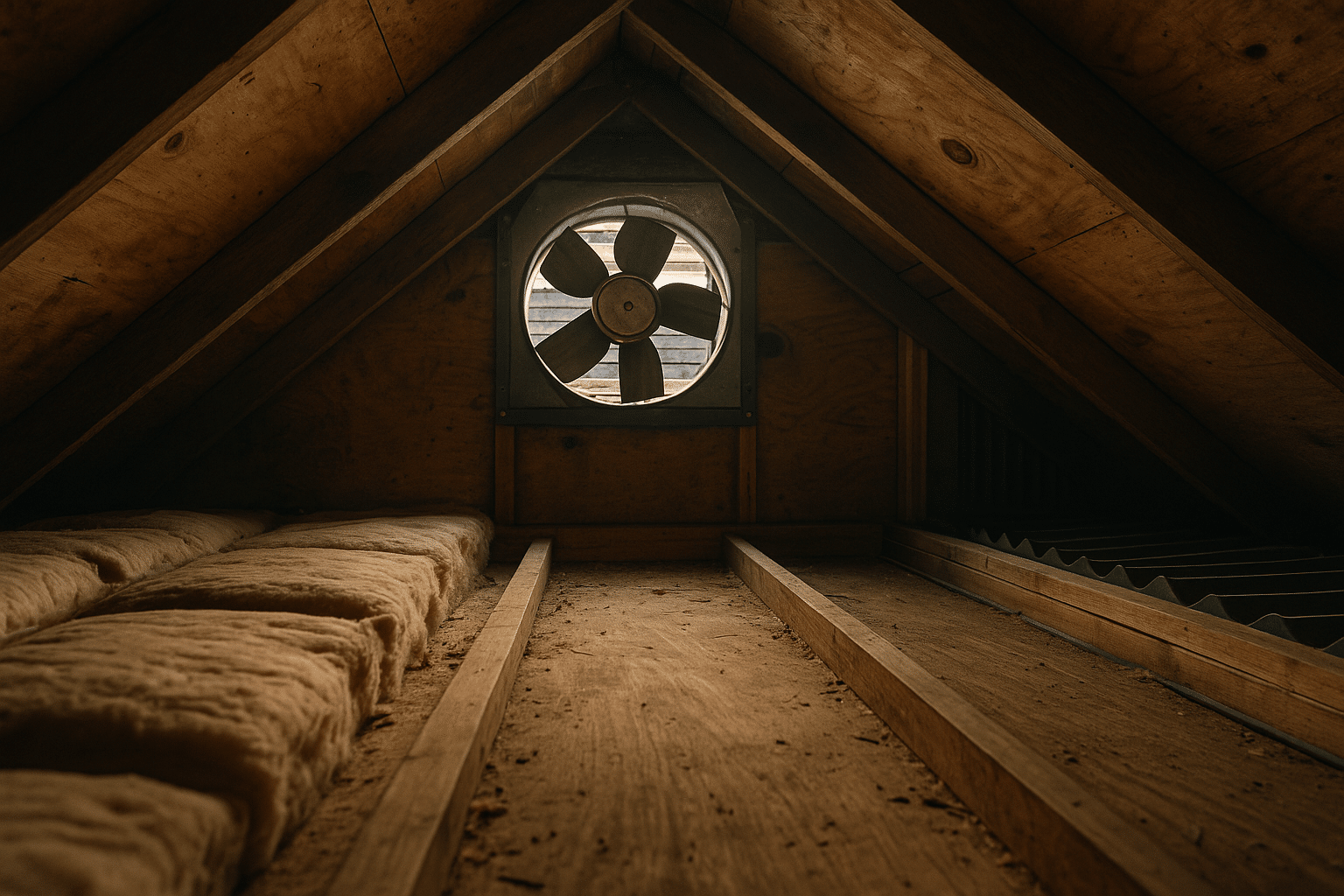

Stump grinding turns a static tripping hazard into a manageable bed of chips and soil. Unlike full extraction, which lifts the entire root mass and can leave a sizeable crater, grinding mills the stump and main surface roots into mulch on site. The process typically starts with utility locating, a safety sweep for stones or rebar, and a flush cut to reduce height. A grinder then makes gradual sweeps, shaving layers until the target depth is reached.

Depth depends on goals. For lawn restoration, 15–30 cm (6–12 in) typically allows enough soil cover to prevent regrowth from most species. If you plan to replant a small tree or shrub in the vicinity, grinding 20–45 cm (8–18 in) and expanding the grind radius to chase larger surface roots can help. The grind circle often needs to extend beyond the visible stump by 15–25 cm (6–10 in) to capture buttress roots. Afterward, crews rake chips into a mound slightly above grade; as chips settle over a few weeks, topping with soil and compost creates stable footing for sod or seed.

Comparing options:

– Grinding: fast, cost-efficient in tight spaces, minimal soil disturbance. Chips act as temporary mulch, though mixing with topsoil improves planting outcomes.

– Full removal: eliminates major roots but requires bigger equipment, more time, and significant backfill to restore grade.

– Chemical decay accelerants: long timelines, variable results, and potential restrictions. Often used only when time—not near-term usability—is the priority.

Benefits extend beyond appearance. Removing the stump reduces trip risk, frees mower paths, and can reduce habitat for certain wood-decaying fungi and boring insects. It also clarifies drainage patterns; a ground stump won’t shed water onto beds like a tall pedestal of wood. Cost typically correlates with stump diameter at grade, wood density, access constraints, and presence of rocks. As a rough planning note, hardwoods grind slower than many softwoods, and limited access that prevents a tracked machine from entering can increase labor. For replanting, shifting the new tree a meter or more from the old stump site helps avoid pockets of decaying wood and gives roots mineral soil to explore. Patience pays: a short wait for settlement and soil prep turns a once-stubborn stump into the foundation of your next planting.

Landscaping After the Grind: Soil Recovery, Sunlight Shifts, and Design

Once the stump is ground, the site enters a transition phase. The canopy that used to filter sun and intercept rain is gone, so microclimates change: beds receive more light, evaporation increases, and turf may dry faster. Equipment may have compacted soil, reducing infiltration and oxygen. Addressing these shifts early keeps the landscape healthy and prevents maintenance headaches.

Start with soil rehabilitation. Remove excess chips where you intend to grow lawn or perennials; a modest layer can be useful as mulch, but too many chips tie up nitrogen as they decompose. Blend in 2–5 cm (1–2 in) of compost and mineral topsoil, then grade for gentle runoff. In compacted areas, de-compact with a fork to 15–20 cm or use air-excavation tools around feeder roots of nearby trees. Target a mulch layer of 5–7 cm (2–3 in) in beds, keeping it a hand’s width away from trunks to avoid moisture against bark.

Design adapts to new light and wind. Where shade-loving plants once thrived, pivot to sun-tolerant perennials, native grasses, or heat-resilient shrubs. If privacy was lost, consider a layered screen combining small trees, shrubs, and groundcovers; staggered planting creates depth and filters views without forming a maintenance-heavy wall. Pathways or seating can occupy the former stump circle, especially if grade and drainage are now smooth. Think in patches rather than isolated plants: repeating species in groups of three to five looks intentional and reduces visual clutter.

Useful checkpoints:

– Observe sun patterns for a week before finalizing plant choices.

– Fix drainage first; planting into soggy or compacted soil invites problems.

– Choose plants that match soil, moisture, and light rather than forcing a favorite to fit.

Lawns need a consistent establishment routine: level the area, seed with a mix suited to your region, and water lightly but frequently until germination. Afterward, shift to deeper, less frequent watering to train roots downward. Beds benefit from drip irrigation zones that target soil, not foliage, reducing disease pressure. With a thoughtful reset, the site of a removal becomes an asset: a brighter corner for edible beds, a small pollinator meadow, or a calm seating nook edged by low shrubs. The key is to let the landscape respond to the new conditions rather than recreating what no longer fits.

Arboriculture for the Long Term: Right Tree, Right Place, Right Care

Removal and grinding are moments in a longer story of canopy stewardship. The next chapter begins with selection and planting. Choose species that fit mature size, soil type, sun exposure, and utility clearance; many urban conflicts start with an enthusiastic planting that outgrows its space. Diversity matters for resilience: a common guideline suggests limiting any single species to roughly 10%, any genus to 20%, and any family to 30% of your plant palette to reduce pest and storm vulnerability across the site.

Planting technique influences decades of growth. Dig a hole two to three times wider than the root ball and just as deep, set the root flare at or slightly above grade, and loosen circling roots. Backfill with the same soil you removed; amendments belong in the top layer as compost or mulch, not in the hole where they can create a bathtub effect. Stake only if necessary for wind exposure, and remove stakes within a season. Water newly planted trees with roughly 10–20 liters (2–5 gallons) per week per caliper inch during the first growing season, adjusting for rain and heat. A wide mulch ring retains moisture and protects from mower and string trimmer injuries.

Pruning is proactive, not reactive. Structural pruning in the first five years trains a strong central leader, balances scaffold branches, and prevents future conflicts with buildings or walkways. Avoid topping; it invites decay and weakly attached sprouts. Time cuts to minimize stress and disease risk, and use clean, sharp tools with proper cut placement outside the branch collar to aid natural sealing. For mature trees, periodic inspections catch early signs of stress: dieback in the crown, cracks at unions, fungal conks at the base, or soil heaving after storms.

Nurturing soil biology is fundamental. Leaf litter, compost, and mulch feed microbes that support root health, improve structure, and increase water-holding capacity. Protect the critical root zone from compaction by limiting vehicle traffic and heavy storage; install permeable paths where access is needed. Integrate integrated pest management: select tolerant species, scout regularly, encourage beneficial insects, and intervene with targeted measures only when thresholds are met.

Put it together and the pattern is clear: plan removals carefully, grind stumps to reclaim space, rebuild soil and design with intention, then plant and tend a diverse, site-appropriate canopy. Over time, the yard becomes more than a collection of plants—it functions as green infrastructure that shades, filters, holds soil, and makes daily life calmer. That is arboriculture’s quiet promise: small, correct steps now for decades of healthy growth.